Notes: socialization, the process by which individuals learn the appropriate attitudes and behaviors within a culture (HP).

The previously accepted idea was that the self is biologically derived and individually constructed, but the basic concept arose that the self is a compilation of social experiences and interactions. Therefore, the self and society are intertwined, and sociologists, such as George Herbert Mead, went so far as to say that there could not be a self without society.

Were you born with your personhood intact (nature), or was it gradually formed through your social interactions with your parents, teachers, and friends (nurture)? Most psychologists, behaviorists, and sociologists conclude that the answer is a combination of nature and nurture. Within sociology, the focus is on social and environmental conditions rather than heredity and genetic predispositions.

At the micro level, the focus is on the self, an individual’s nature and identity resulting from reflections on social interactions. The self is socially constructed through your conversations and social activities.

Mead divided the self into the “I,” the unsocialized or acting self, made up of personal desires and needs, and the “me,” the social self, made up of the internalized attitudes of others. The “me” is learned early in life through interactions with others and the environment. The “I” distinguishes the self from others due to one’s spontaneity and impulses. Without the “I,” you would only be a reflection of the attitudes of the general society. The “I” reacts to the “me” in each social context and interaction.

In the preparatory stage, imitation of others, an infant merely imitates surrounding people. As infants grow, they use symbols such as gestures and words to communicate. Children in this stage are very self-centered, and the self has not developed. The play stage, pretending to be other people, incorporates role-playing. Do you remember playing house or pretending to be a police officer? This stage involves assuming the perspective of others one at a time, and according to Mead, this is when children first begin to show signs of developing a self. As a child, you assumed the individual roles of significant others, individuals who are important to the development of self, which meant you thought about how they wanted you to behave. The game stage, taking the role of multiple people at one time, normally occurs before the age of 10. By this time, you are able to imagine what other members of society expect of you. Mead labeled this the generalized other, the process of internalizing societal norms and expectations. This process continues for a lifetime. Although you are most often unaware of it, you have a kind of internal conversation with the generalized other each time you think about an action.

hese experiences and how we react to them can be analyzed sociologically. Charles Horton Cooley (1864–1929) described this process as the looking-glass self, the process of imagining the reaction of others toward oneself (HP) (Cooley 1902). He states that we look to others to create an understanding of self. Here is how it works: first, we imagine how we seemingly appear to others, and next, we imagine the judgment of that appearance by others.

The looking-glass self (C-19) is a process that you experience daily. You often make split-second decisions about your appearance, such as “I look stunning!” or “I look terrible since I came to class in sweatpants, and my hair is a mess.” You may imagine that others in your class think you look unattractive without your usual makeup and fashionable wardrobe. Or you may imagine that no one cares how you look and will not even notice you. In both cases, you are developing a sense of self for that moment.

- Imagine how you appear to others.

- Imagine the judgment of your appearance by others.

- Determine how the process influences your self by combining how you imagine you appear to others and their judgments of your appearance.

the agents of socialization, individuals, groups, and institutions that influence the attitudes and behaviors of members of society (C-19), are structural components of society that significantly influence who you are today and who you will become. These agents include family, peers, school, media, religion, work, and government. As an agent, the media has probably influenced what you wear, the television shows you watch, the music you listen to, and the products you buy.

Sociologists often explain socialization within families with social learning theory, the process of learning from one another in a social context as a result of observation and imitation.

The family (HP) is the primary agent of socialization.

Our parents are our most significant agents of socialization early in life until school, peers, and work begin to influence us heavily. One of parents’ biggest concerns is their child hanging around the wrong friends and caving into negative pressure from peer groups, social groups consisting of members with similar interests, social rank, and ages. Popular adolescents are labeled as high-status youth, those who are viewed as being popular among peers. There are two categories of high-status youth: those who are genuinely well-liked by their peers and engage in predominantly prosocial behaviors and those who are seen as popular but not necessarily well-liked (Cillessen and Rose 2005).

hese examples are part of the hidden curriculum, the unintentional education of students in the ideals and ways of being in society. This hidden curriculum may have even influenced your college major.

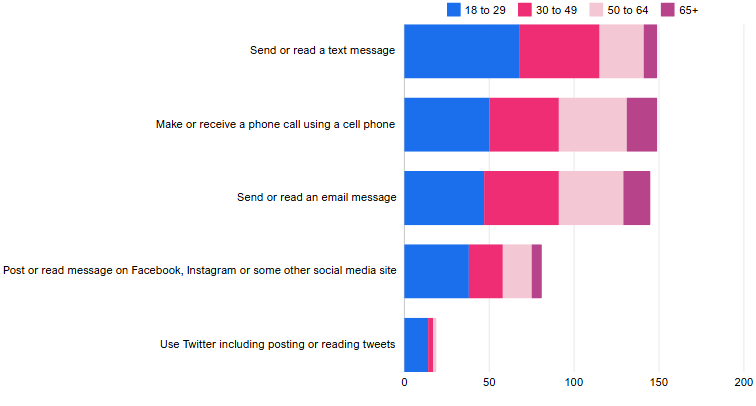

Born in and after the 1990s, digital natives, individuals born after the widespread adoption of technology, are those individuals who have always experienced a digital world. On the other hand, your authors are digital immigrants, individuals born before the widespread adoption of technology.

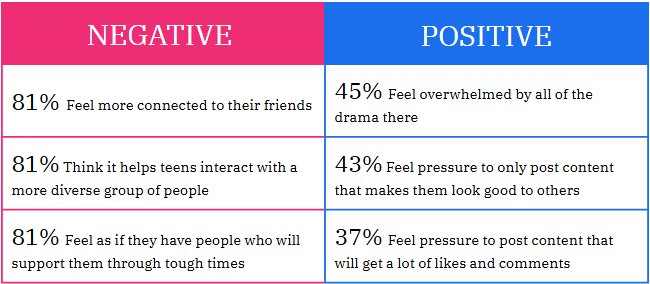

The amount of social media consumed, how children and adolescents use it, and the immediate and long-term effects of such consumption may be alarming to sociologists and other researchers. But it is important not to overlook the positive aspects of social media. For example, staying connected with friends and family, making new friends, and sharing pictures and ideas are just a few ways teenagers benefit from social media. Additional benefits for teenagers include:

- opportunities for online community, political, and philanthropic engagement

- accessing health information

- growth of ideas from the creation of blogs and videos, and

- fostering individual identity and unique social skills (O’Keefe and Clarke-Pearson 2011).

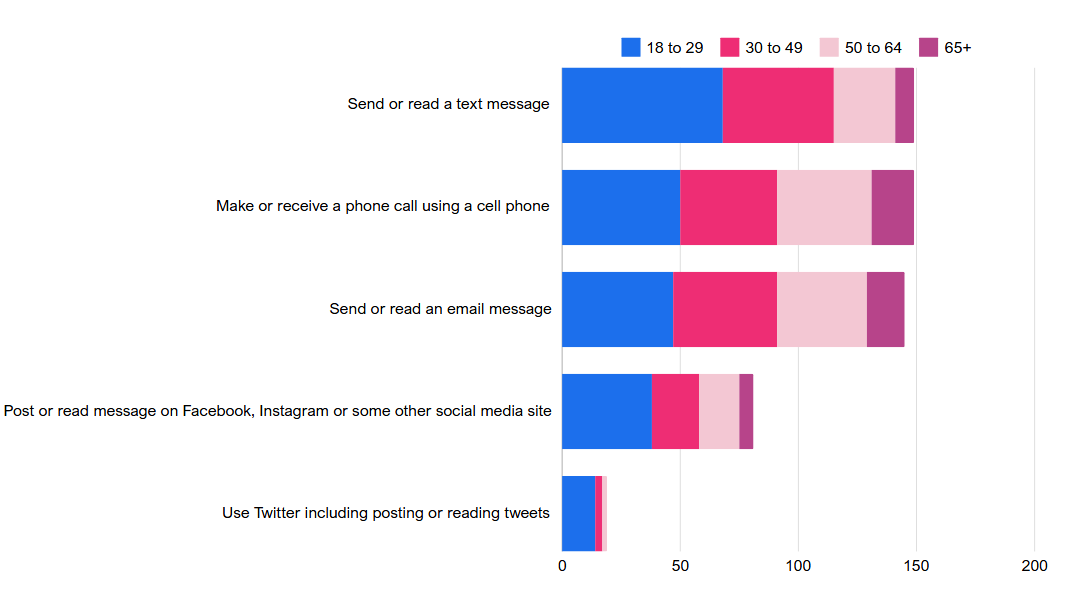

College students are just as connected to social media as teenagers, with 94 percent of 18-to-24-year-olds using YouTube, 78 percent using Snapchat, and 71 percent using Instagram (Pew Research Center 2018). The typical cellphone user touches their cellphone 2,617 times daily (2.42 hours usage), and the heavy users (top 10 percent) touch their phones 5,400 times daily (3.75 hours usage) (Dscout 2016). The average college student checks their cell phone 11 times a day while in class; only 8 percent indicate they do not check their phone at that time (McCoy 2016).

Sometimes families fail to socialize their children to the standards considered the norm in society. What happens when families completely fail to socialize with their children? While this may occur for various reasons, extreme cases result in what sociologists call feral children, children who are isolated and neglected such that they are raised without socialization. Thankfully, while feral children are rare, the cases that have come to light give us insight into how important socialization and human interaction are to the well-being of the individual and society.

Genie was a feral child who could not talk and barely walk.

The social class of the parents plays a key role in the socialization of children.

An American Academy of Pediatrics study reported that 90 percent of parents said their children under age two watch some form of electronic media. By age three, one-third of children have a TV in their bedroom and watch TV one to two hours per day (American Academy of Pediatrics 2011). The study reported the following:

- There is a lack of evidence supporting the educational and developmental benefits of using media for children under two years of age.

- There are potential adverse health and developmental effects of media use for children under two years of age.

- There are adverse effects of parental media use (background media) on children under two years of age.

Recruits who have accidentally or intentionally done something wrong are often confronted with a type of public punishment or humiliation that sociologists call a degradation ceremony, an event, ceremony, or rite of passage used to break down people and make them more accepting of a total institution.

The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, sociologist Erving Goffman explained these performances with the concept of dramaturgy, the theory that we are all actors on the stage of life, and as such, we divide our world based on what we do and do not let the others see of us (Goffman 1956).

According to Goffman’s theory, our world is divided into two areas. The first is what we let the world see, our front stage, a person’s public life that they reveal to the world. In juxtaposition, we try not to let the world see our backstage, a person’s private world that they choose not to reveal (C-19).

He contends that the theory has a third component, the notion of impression management, an effort to control the impression others have of us. By engaging in impression management, we are not only being selective about what we reveal to the world but also making a decision, consciously or otherwise, about how much of our personal troubles we are willing to make public issues. The socialization process plays a key role in our understanding of what to keep private and what to make public.

Some people are uncomfortable being patted down because of their socialization about personal space. How much space do you feel comfortable having between yourself and someone else? Your answer to the question reflects how you were socialized in your particular culture. Anthropologist Edward Hall addressed the issue of personal space with his work on Proxemic Theory (Brown 2011). His research involved studying distance zones, the amount of space we are socialized to feel comfortable having between ourselves and others (HP). Hall identified four distance zones (C-19) in the United States:

- Intimate (0–18 inches): reserved for people who know you really well, such as your significant other, family, and close friends.

- Personal (18 inches–4 feet): reserved for less intimate social interactions like student and teacher, or therapist and patient.

- Social (4–12 feet): reserved for casual acquaintances and strangers.

- Public (12 feet and beyond): reserved for impersonal interactions like those involving public speakers and stage performances.

We can study an individual’s socialization experience at different intervals based on the norms of their society. This approach, known as the life course perspective, refers to a series of social changes that a person experiences over the course of their lifetime.